New analysis finds big impacts in oil producing states

For decades, oil and gas industry growth has been enabled by slashing protections for water. Some of the most common forms of oil and gas production benefit from federal loopholes and policies that remove water protections in order to streamline permitting and cut operational costs. The aquifer exemption program in the Safe Drinking Water Act’s (SDWA) Underground Injection Control (UIC) program, and the notorious Halliburton loophole that removed SDWA protections for hydraulic fracturing operations, are two of the most egregious examples. These regulatory exemptions allow oil and gas companies to operate in ways that put water at risk, and free them of the oversight needed for regulators to prevent contamination. The Trump Administration’s Dirty Water Rule, which would strip federal protections from millions of stream miles and more than half our nation’s wetlands, is another loophole for oil and gas companies that would streamline wastewater disposal options and allow for more unchecked discharges. Redefining what water EPA protects was the primary Trump campaign environmental rollback proposal. It’s one of many giveaways to the fossil fuel industry, and its impacts should be viewed in that context.

While the biggest cheerleaders for gutting the Clean Water Act have been big agribusiness, the oil and gas industry has been quietly lobbying to slash protections as well, weighing in to oppose the 2015 Clean Water Rule, and continuing to work behind the scenes, lobbying to repeal and replace it with the Dirty Water Rule. Perusing lobbying expenditure reports for the American Petroleum Institute (API) (the largest oil and gas trade association in the country), shows massive lobbying expenditures that include working to redefine Waters of the US. API is also a member of the ironically named Waters Advocacy Coalition (WAC), one of the primary front groups working to weaken the Clean Water Act. WAC doesn’t list its coalition members on its website (shady!), but API and several other fossil fuel entities are listed on comments such as these, calling for a repeal of the Clean Water Rule.

The Dirty Water Rule will have big impacts in oil and gas states

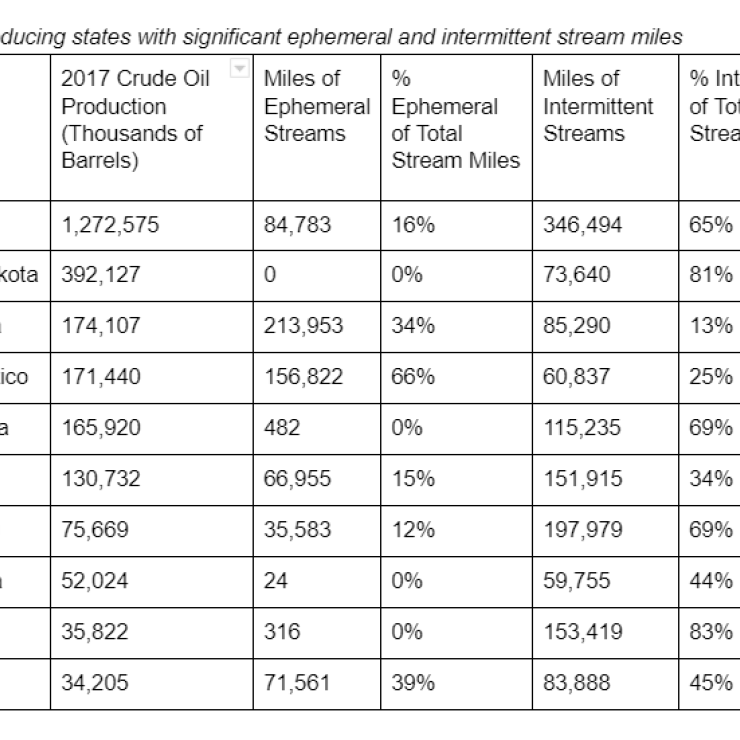

Ten of the 11 largest oil producing states (with the exception of # 2 Alaska) have significant portions of stream miles that would lose Clean Water Act protection under the proposal. As currently proposed, the Dirty Water Rule would eliminate protections for “ephemeral” streams - meaning those that flow only after heavy rain events. And EPA invited comment on whether to also strip protections for “intermittent” streams - which flow on a seasonal basis, but not year round. As noted in EPA’s own economic analysis of the Dirty Water Rule, these major oil states could lose protections for a significant share of overall stream miles, potentially unleashing a torrent of produced water into these streams.

Sources: Crude oil production - US Energy Information Administration, Stream Data - US EPA, p. 219

More oil and gas = more dirty wastewater

While the primary disposal method of produced water is underground injection, either for disposal or enhanced recovery, operators are increasingly looking for alternative disposal options. As injection capacity may be reaching its limits in some places, and increased regulatory scrutiny on the Underground Injection Control program in others, surface disposal and reuse options are viewed by the industry as necessary in order to keep producing hydrocarbons at its current breakneck pace. Without anywhere to put all that wastewater, oil and gas companies can’t keep bringing oil and gas to the surface. Finding new disposal options is core to their business model.

The Clean Water Act and produced water

In order to discharge produced water, or any other pollutant, from a point source into a “Water of the United States”, a discharger must obtain a Clean Water Act permit as part of the National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES). While oil and gas companies currently can obtain a permit to discharge directly into Waters of the US, they must demonstrate that their discharge meets the standards set out in the “Effluent Limitation Guidelines” (ELGs), a Clean Water Act program that regulates discharges for different industries. Depending on the type of wastewater, treatment facility, and location, there are limits to the ways the the industry can get rid of their waste. This piece by Environmental Defense Fund includes a good overview of the rules for produced water.

One major restriction on discharge is a result of Clean Water Action’s 2015/16 victory in pushing Obama’s EPA to finalize an update to the ELG program that prohibited discharge of “unconventional” wastewater (read: from fracking operations) to municipal wastewater plants, or publicly owned treatment works (POTWs). “Conventional” wastewater, on the other hand, despite exhibiting many of the same characteristics as unconventional waste, can still be sent to a POTW. And with a permit, produced water may be sent to centralized waste treatment (CWT) plants - despite EPA recently identifying major questions about the safety of this practice.

However, if a stream or wetland loses status as a water of the US, none of the protections, limitations, or Clean Water Act permitting requirements would apply. The ELGs, like all Clean Water Act programs, can only protect waters that have jurisdiction under the Act. This would give oil and gas companies more places (and fewer regulatory hurdles) to dump their waste. This is the key reason oil and gas producers support the Dirty Water Rule.

Industry wants more surface disposal options

With industry feeling the wastewater squeeze, they see the opportunities in the closest river or stream, but that pesky Clean Water Act is currently holding them back.

EPA is here to help...the oil and gas industry

The Trump Administration doesn’t hide the fact that it serves the fossil fuel industry. And industry players think their level of access is pretty great too. At the request of industry trade groups, EPA has begun to lay the groundwork for rolling back ELG requirements. EPA will publish a study of produced water, with the explicit goal of exploring possible regulatory changes to streamline surface disposal and reuse options. We know that industry wants relaxed standards on surface discharge because they have been asking for them. For example, the Independent Petroleum Association of America (IPAA) Executive Vice President Lee Fuller sent a request to repeal the zero discharge standard from POTWs in a direct request to EPA Chief of Staff Ryan Jackson in an email on April 6, 2017.

New Mexico (under former Republican Governor Martinez), where the Permian Basin boom has vaulted the state to third in the country in oil production in 2018, has been leading the charge in pushing for more disposal and reuse options for produced water. The state teamed up with EPA to publish a white paper to outline discharge options, and got the first speaking slot at a recent EPA hearing on the produced water study.

While the weakening of ELGs would be a boon to the industry, an even bigger prize would be slashing the entire scope of the Clean Water Act, enabling not just more discharge, but also clearing the way for more pipelines.

Help us push back against this reckless proposal.

The Dirty Water Rule is bad for drinking water. It’s bad for birds, fish, and wildlife. It’s bad for small businesses. But it’s good for the oil and gas industry. EPA should be doing MORE to protect us from fossil fuel development. Not less.